The Master of Development Engineering program graduated its fourth cohort last month, expanding the ranks of professional changemakers addressing complex challenges in low-resource settings around the world.

Families of the 27 newly minted graduates gathered in Banatao Auditorium for an intimate commencement ceremony before moving to Blum Hall, home of the MDevEng program, to celebrate.

“The gift of Development Engineering, to me, is learning to think about the technical and the human in the same hand,” commencement speaker Pratiyush Singh told his peers and their guests. “I leave with a way of seeing: one that showed me that who I am and what I want to do are not competing worlds, but the same story.”

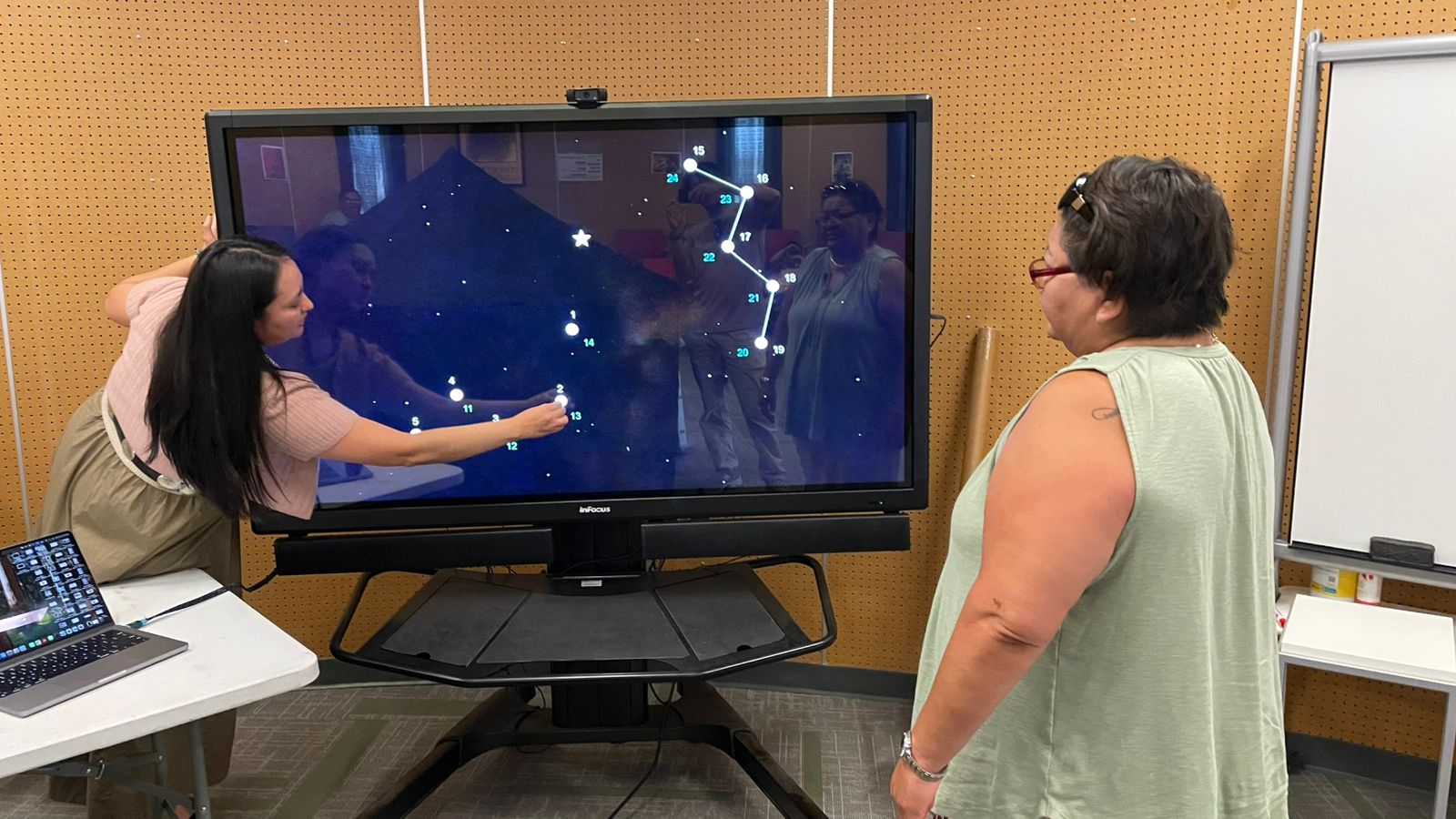

The Class of 2025 studied water-quality solutions for Passamaquoddy communities in Maine, conducted a lifecycle sustainability assessment of post-consumer PET recycling in Uganda, worked on AI-based portable diagnostics for neglected tropical diseases, and envisioned what a car-free San Francisco would need and look like — among many other projects, research, innovations, and efforts to apply engineering and other fields for the benefit of people and planet.

And they pursued this work while often-unprecedented challenges to higher education, research, and the very means and goals of Development Engineering were unfolding over the cohort’s three semesters at Berkeley.

“This year has been an incredibly difficult year to think about justice and development: one marked by funding cuts, institutional uncertainty, and the painful realization that the very work we’re trained to do often stands on fragile institutions,” said Singh, whose capstone project focused on shifting mortality burdens among vulnerable populations facing extreme heat in Mexico. “If anything, this fracture makes our work much more urgent, much more necessary.

“Justice is never guaranteed by institutions,” he added. “It survives because people, hopefully us, choose to carry it forward.”

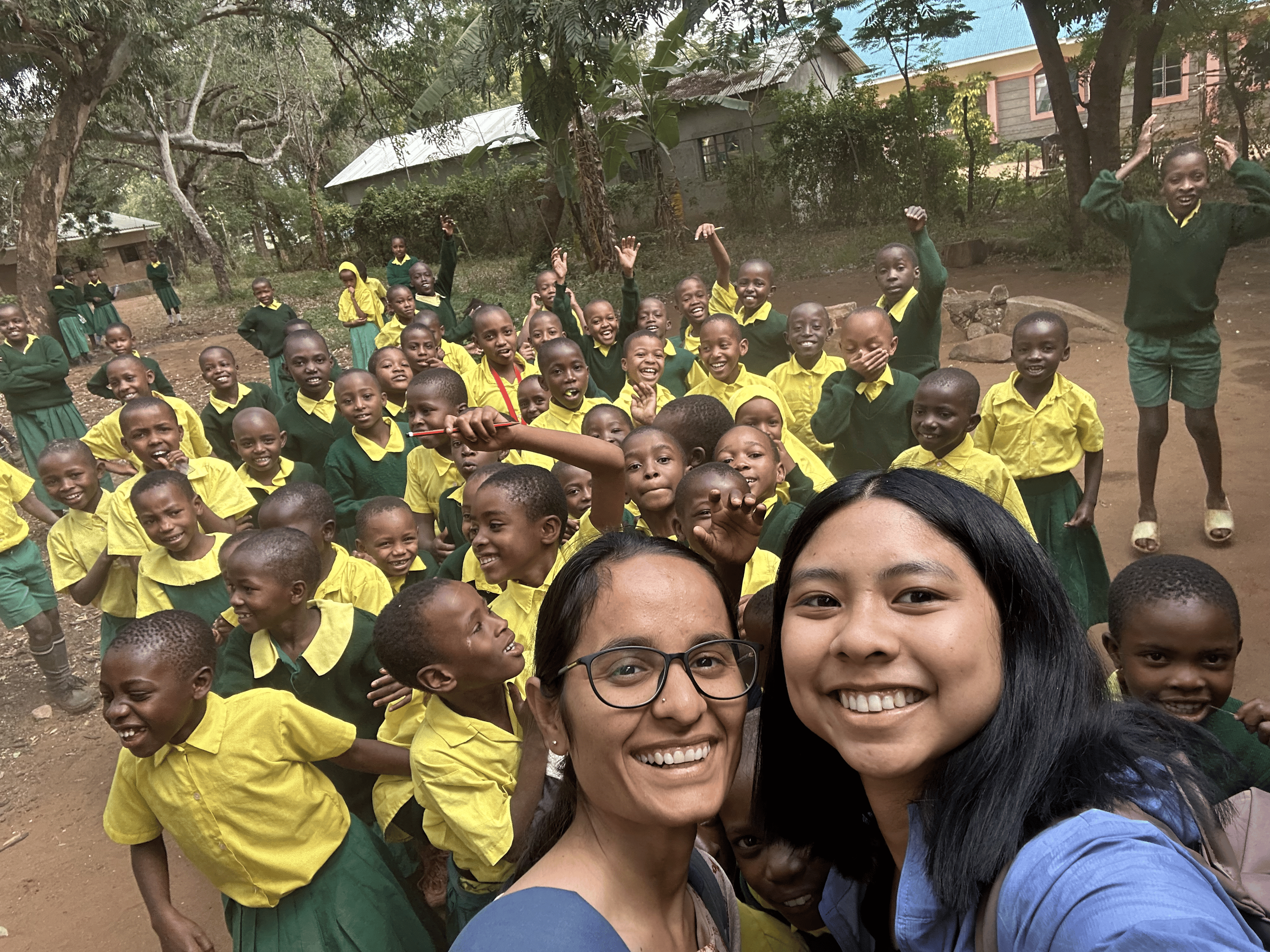

Paige Balcom, who received her PhD designated emphasis in Development Engineering in 2022, returned to Berkeley for the first time since earning her degree to give the evening’s keynote address.

She shared some of the challenges that the social enterprise she co-founded, Taktaka Plastics, has faced, and how managing and motivating people — a process built on trust — is a more difficult component of DevEng work than the technical issues.

DevEng “is long-game work,” she said. “And at the center of that long game is trust.”

Trust is “built through listening, showing up consistently, and involving the stakeholders of partners, not just the beneficiaries. Trust is built through co-design, through transparency, and doing what you say you’re going to do,” said Balcom. “And trust is fragile; it can be damaged quickly: by rushing, by ignoring local knowledge, or by prioritizing short-term wins over long-term relationships.

“But when stakeholders trust you enough to give their honest feedback, and you authentically incorporate their input and design,” she said, “the solution will be much better, and it will have a much higher chance of actually being used long term.”

Balcom closed her speech with some final advice to a group pursuing Singh’s vision of “choosing to carry [justice] forward.”

“Remember your motives,” she concluded. “Be patient. Build trust. Play the long game. Steward your degree with humility.”